- Home

- Alexander Roy

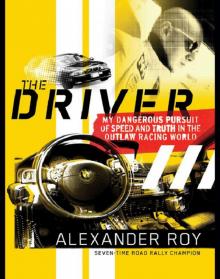

The Driver

The Driver Read online

The Driver

MY DANGEROUS PURSUIT OF SPEED AND TRUTH IN THE OUTLAW RACING WORLD

Alexander Roy

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO

Owen and Aidan Weismann

Julian Lai

Amelia Rose Karasinski

Ella Simon Kruntschev

Mia Acutt

Jack Kenny (RCAF)

and my father

We are, all of us, growing volcanoes that approach the hour of their eruption; but how near or distant that is, nobody knows.

—FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Contents

EPIGRAPH

PROLOGUE

PART I RENDEZVOUS

1. THE DIVINITY OF PURPOSE

2. RENDEZVOUS

3. GOD IS SPEED

4. CROSSING THE RUBICON

5. THE WORLD’S BEST BAD IDEA OF ALL TIME

PART II GUMBALL 2003

6. I, SPY

7. DIE FIEND-PILOTEN

8. DORSIA

9. THE ELEVENTH HOUR

10. TWO MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

11. HOW OLD THOSE GIRLS WERE

12. GUMBALL!

13. THE HEAD OF THE SNAKE

14. REQUIEM FOR THE BLUE MERCEDES

15. THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S DAUGHTER AND THE SHERIFF’S WIFE

16. WHAT YOU GET FOR THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

17. THE UNLUCKIEST LAMBORGHINI OWNER IN THE WORLD

18. I CAN’T BELIEVE THE KING OF MOROCCO DID THAT

PART III BULLRUN

19. THE BED OF MY ENEMY’S AVALANCHE

20. WHATEVER IT COSTS

21. CORY

PHOTOGRAPHIC INSERT

PART IV THE GOLDEN AGE

22. I THINK THOSE PRIESTS WERE LYING

23. THE COEFFICIENT OF DANGER

24. TOTAL WAR: THE BATTLE OF ROME

PART V THE DRIVER

25. THE SHERPA FROM DALLAS

26. BADIDEA.COM

27. THE WORST ROAD TRIP OF ALL TIME

28. THE LONGEST TUNNEL IN AMERICA

29. DRIVEPLAN 1 ALPHA [ASSAULT FINAL]

30. NAKED DAYTIME RUNNING

31. TIME IS THE DEVIL

32. THE PATRON SAINT OF NONVIOLENT AND UNPROFITABLE CRIMES

33. THE DRIVER

34. THE STORM CHASERS

35. THE OMIGOD OF WRONG

36. COUNTDOWN

37. THE BRAVEST DRIVER I EVER MET

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Prologue

“Alex Roy from Gumball!?” said Mark, client advisor at Jackie Cooper BMW in Oklahoma City. “Me and the guys couldn’t believe it when we Googled you. We knew something was up when we saw all the antennas and gear inside. Totally awesome, man. Definitely the coolest car we’ve ever had in here. All the customers who come by ask about it. What are you doing in Oklahoma?”

“It’s a long story, but listen, I’m just boarding a flight out right now. How quickly can you get that car on a truck back to New York? Money is no object. I need it back in time to ship to Europe for Gumball.”

“I’d say…within twenty-four hours. Let me make a couple of calls.”

I sat back for the surreal two-hour and fifty-four-minute flight to L.A., during which I would survey the 1,342 miles I’d hoped to cross by car in fourteen hours and eight minutes.

My phone rang. I caught the eye of the flight attendant three rows ahead, having just started her pretakeoff survey of bag placement, seat belt tautness, and—

It was Mark from BMW. “Mark, I’ve got five seconds to takeoff, so whatever it costs, just do it.”

“Alex—”

The flight attendant approached. “Mark, whatever it costs—”

“I’m sorry,” said the attendant, “but you must turn that off now.”

“Mark, just do it.”

“Sir! If you don’t turn off that phone—”

“Alex, the police are here—”

“—I will call security!”

“Hello? Alex, the police want to know where you are and—”

I dry heaved, dropping the phone in my lap.

“Thank you, sir!” She walked away. My hands shook as I lifted the phone. Mark was gone. I turned off the ringer. My thumbs vibrated like tuning forks as I laboriously typed my attorney, Seth, a priority e-mail, ending with they must NOT get inside that car. I hit send just as the plane began taxiing. If my stomach hadn’t been empty, I’d have thrown up.

Part I Rendezvous

CHAPTER 1

The Divinity of Purpose

DECEMBER 1999

It was a gorgeous morning, heaps of snow having escaped the streets’ salting in the wake of the previous night’s storm, their knee-high peaks not yet capped with soot from passing cars and trucks.

My cell phone rang as I descended the subway station steps at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Bleecker Street, mere seconds before I would have disappeared into the station and out of range for the next half hour.

“Is this Alexander Roy?”

There was only one reason for such a call.

“This is Dr. Johnson at Beth Israel Hospital.”

The world slowed.

“As your father’s medical-care proxy, you must give permission for any time-critical procedure during a life-threatening or…Mr. Roy? Mr. Roy, can you hear me?”

The bus rumbling mere feet away, the cacophony of voices echoing off the subway station’s tiled walls just ahead, the deep hot rushing roar of air out of the station entrance as a train pulled in—all were muted by the gravity of events to which I could only react, and never control.

“Mr. Roy?”

“I’ll be there in fifteen minutes.”

“There’s no time. We need your permission to perform an emergency tracheostomy immediately.”

“Or else?”

“Your father will die.”

OCTOBER 1999

My father was very secretive about his past. While I was a child, the notion of my climbing up his leg to ask a question—to scale the seemingly indomitable mountain that was my father—was terrifying.

My father had always described himself as a lion, and so had everyone else. He’d lost everything during the Second World War—his brother, his friends, his childhood home—and fled with his surviving family to New York City. He joined the U.S. Army at seventeen, landed at Normandy, was shot and wounded twice, and rode with the lead units into Buchenwald concentration camp. After the war he started life anew, founded the family business in 1954, met my mother in 1970, had two sons he sent to private school, bought a Cadillac, and earned (and saved) enough for us to live comfortably. Even his enemies—and these were restricted to business competitors—respected him, trading insults over the phone every week for decades. He spoke fluent French and Spanish, and conversational German, Russian, and Polish. All agreed he was a gifted painter, photographer, and pianist. My brother and I knew better than to interrupt his weekday postwork relaxation time, during which he plucked at the precious custom-made flamenco guitar he’d bought in Seville. He loved work, and intended to work until the day he died. Surrender was inconceivable.

I never believed it possible that he could be withered by cancer, his deep radio-commercial-grade voice cracking from multiple surgeries and chemotherapy, lying in a hospital bed 15 minutes from where we’d lived for more than twenty years. I’d always assumed he’d live to see me married with children. That was his greatest wish.

My greatest wish was for him to reveal what he’d really done between the war and his meeting my mother, a nearly twenty-five-year gap that had been left largely unexplained. My mother’s curiosity went further, as the frequen

t business trips he’d taken when they first met had continued through the late 1970s, ending abruptly in 1980.

Time was now running out.

Radioactive pellets had been placed in his neck to fight a cancerous tumor, and the resultant swelling made breathing painfully difficult. The doctors recommended, and my father consented to, a tracheostomy—whereby a hole was cut in his neck and a breathing tube inserted down his throat. His body, already greatly weakened by months of treatment, reacted badly to the procedure, and I spent long nights beside his hospital bed watching him sleep under heavy sedation.

The swelling persisted for weeks after the pellets were removed, and in heavy-lidded moments of near wakefulness his feet danced slowly under the sheets, both hands raised like claws.

“I wonder what he’s dreaming about,” said the wife of the patient in the neighboring bed.

“Driving,” I said.

Once the tube was finally removed, he began daily, mostly unconscious visits to a hyperbaric oxygen chamber intended to accelerate the closure and healing of his throat.

“He won’t be able to speak for some time,” one doctor warned as he handed me a pad and paper, “but you can try this.”

My father’s eyes darted wildly during his first few days of wakefulness, his hands too shaky for anything but scrawling gashes through the paper. Clarity slowly returned to his gestures, and he resumed looking me in the eyes and nodding as I asked him yes/no questions about the business I knew he missed. He struggled to push words up through his ragged, constricted throat. I stared at his mouth and raced like an auctioneer through phrases I wanted to spare him the pain of attempting to utter.

He pointed at the pad and paper, wrote furiously, then turned the pad toward me.

Throat

Dry

Air

Fire

“I’ll get you more water,” I said, bringing the straw to his mouth.

He swiped it aside angrily and wrote again.

Operation

“The tracheostomy?” He nodded. “What about it?”

Never

Again

Pain

“You don’t want to have a tracheostomy again?”

Prefer

Die

“C’mon,” I said, false optimism tugging at the corners of my mouth. “That’s so unlike you.”

Suddenly and with vicious strength he grabbed my wrist, pulled my face to his, and whispered through quivering lips.

“You…cannot…allow…it.”

“But—” I mouthed in disbelief.

He glowered at me, eyes wide with volcanic anger, and pushed the pad against my chest.

Prefer

Die

DECEMBER 1999

“Mr. Roy!” Dr. Johnson blurted through the phone. “If you can hear me, I need your permission right now if we are to save your father’s life.”

“What,” I said, my eyes welling with tears even as I spoke with literally deadly clarity, “are the odds of his survival without the procedure?”

“Very low. Every passing minute increases the likelihood of oxygen deprivation and brain damage, if he survives.”

“Do it now,” I said, in tears.

MARCH 2000

My father revealed many fascinating things on his deathbed. One was that he’d faked a heart attack in 1995 in order to trick me into moving home to New York from Paris, where I’d been busy finding myself through bartending, wearing a scarf, and attempting to write a novel set in Japan—a country I’d never been to. Another was that he didn’t appear to remember the second tracheostomy, or the ensuing weeks, which was a great relief. Yet another was that he kept a storage room outside the city that had remained unknown to anyone—me, my mother, even Genia, the company bookkeeper of twenty-two years in whom he’d placed sole responsibility for paying the bills he so frequently lost between our mailbox and his office desk.

“What’s so important about the storage room?” I said, interrupting his slow, measured monologue. He’d regained the tone but not the pace of his natural speech.

“A box,” he intoned.

“What’s in it?”

“Pictures.”

“From the war?”

“No.”

“What,” I said, trying to conceal my excitement, “do you want me to do with it?”

He paused far longer than I expected, as if he hadn’t until that very moment decided what to do with this incalculable treasure. He’d already rewritten his will and trust documents innumerable times, having recited from memory every painting, book, and piece of wartime memorabilia he’d amassed, recalling the origin and value of each with scientific precision. His face hardened, and I later came to believe it was then that he’d accepted his impending death, because it was the first time he’d expressed determination not merely to postpone death, but to accomplish one last task before it was too late.

I immediately set off, as per his halting instructions, to retrieve the albums and bring them to my apartment.

“Do not,” he’d said in his James Earl Jones voice as I walked out of his hospital room, “open the box until I tell you. And don’t tell your mother. Don’t tell anyone.”

My father still owned the 1977 Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham he’d bought upon moving to New York from California. It had been driven a mere thousand miles a year for twenty-three years, and he took great pride in being able to park it unlocked anywhere in Manhattan without fear of theft. He admired the soft (I called it hallucinatory) ride and passenger space for seven. I was embarrassed by the broken window controls, the cracked seat leather, the black felt roof lining that sagged on passengers’ heads whenever driving over a bump, and the fact that no self-respecting car thief would steal it even when parked overnight, unlocked, in lower Manhattan. He refused any suggestion that it be replaced, insisting that new cars were too small and uncomfortable at any price. The list of unworthy cars included any new Mercedes, BMW, Cadillac, or Lexus manufactured after 1989. He liked demonstrating the Cadillac’s merits by tricking friends into “going for a ride” during which, five blocks from the garage, he’d claim to have forgotten something at home and the “ride” was cut short. His dream car was a Citroën CX, a teardrop-shaped French car considered quite futuristic when first unveiled in 1974. Rarely ever seen in the United States and out of production for years, the CX’s alleged onetime primacy guaranteed he would never buy another car.

“You have the box?” he said.

“At home.”

“How’s the Cadillac?”

“Terrible,” I said, deadpan.

“I don’t want to hear it. Did you open it?”

“No.”

“If you had, you’d already be asking me.”

“About what happened after the war?”

“Be quiet and listen.”

I braced myself. I had dozens of theories—prior marriage, bad divorce, bigamy, jail, the OSS or CIA. None seemed far-fetched.

“Cannonball Run,” he said, “with Burt Reynolds.”

This was when I suspected he’d not fully recovered from the second tracheostomy. The doctors had warned he might never fully recover, and even if he did, there was the possibility of brain damage. It had always been common for him to drop one conversational thread and pick up another (often parallel but occasionally tangential) topic. Although some considered this the mark of genius, he’d recently begun repeating stories, and this tangent was—

“All true,” he continued, “there really was a Cannonball Run. The nonsense in the movie…most of that happened—” He lurched, almost coughing, which I feared might rupture his IV, ending our conversation as it had several times before.

My eyes darted to the door and the nurses’ desk just beyond.

“I’m…okay,” he groaned.

We shared a silent moment as he gathered his strength, fighting the drug-induced fatigue with anger and resentment.

“Did you know,” he said with a surge of energy, as if he’d jus

t won a temporary, albeit false, victory over his body’s sickly shell, “I had sports cars my whole life?”

“Yes, Dad,” I said. “I knew that.”

“Before you and your brother. A new one every year after I got out of the service. I had everything—Porsches, Ferraris, MGs, Austin-Healeys. Even when the company was doing badly and I slept on your grandparents’ couch. Back then you could drive as fast as you wanted, in Europe, in the States. Those were great days. Then I met your mother. I had a blue Porsche 911 Targa. What a terrific car. She hated it. The noise…the clutch. Then we had you. Then there was the first Cannonball. I knew I had to do it.”

“What?”

“Listen!” he rasped.

“But how come—”

“I didn’t tell you? Because of your mother. She was so upset when she found out. She caught me talking about it with Sascha Orbach. My poor friend Sascha. I think he died. I lost touch with him. I lost touch with him…”

His eyes lost focus. My mind reeled. I wanted—needed—him to proceed.

“Sascha,” he said, “he…tried to get a Citroën CX. Or maybe it was an SM. I can’t remember. Wait…do you know…what the Cannonball record is?”

I shook my head.

The Driver

The Driver